Wind prices plummet again!

The UK’s September 2019 ‘Contracts for Difference’ auction has delivered record low prices, lower than government and industry expectations, sending shockwaves through the sector.

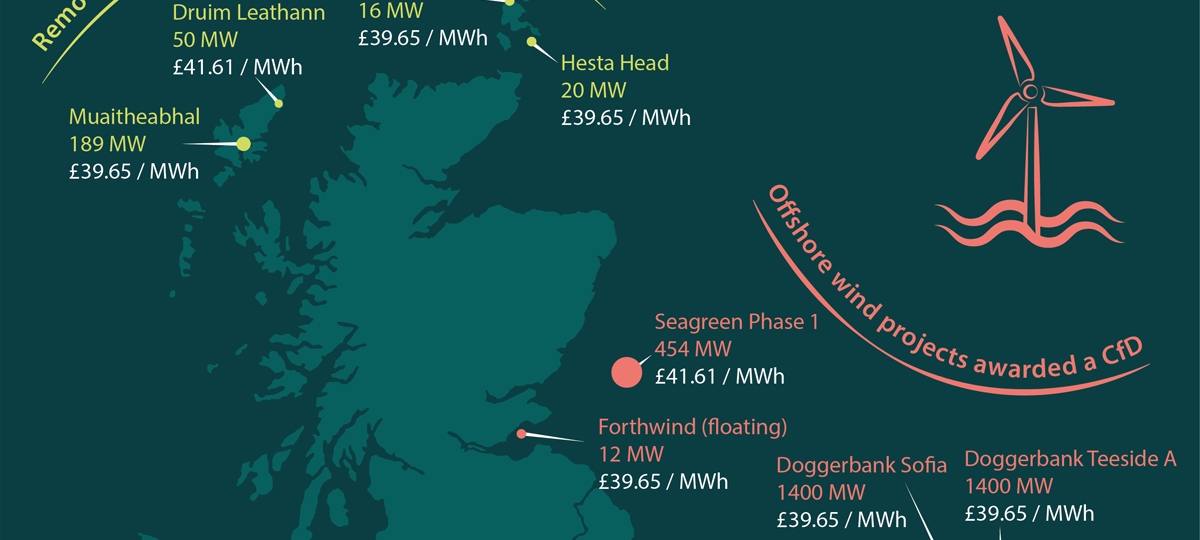

Contracts have been awarded to 12 schemes including six offshore windfarms, totalling 5.5 GW, alongside a further 0.3 GW of onshore windfarm capacity expected to generate ~29 TWh of electricity annually. This is equal to 9% of the UK’s total output in 2018 and is estimated to be sufficient to power 25% of the country’s 26 million homes.

These projects are located in the southern North Sea, close to existing offshore wind farms. As such, the low prices possibly reflect the fact that these sites are cheaper to develop due to being closer to shore, having access to existing port infrastructure and in relatively shallow water.

Low carbon energy can now shake off the accusation of being costly and expensive: these wind developments will “pay back” potentially £246 million per year, once operational.

What is the CfD?

The Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme is the government’s main mechanism for supporting low-carbon electricity generation. A CfD is a long-term contract between the government and an electricity generator guaranteeing a price for the electricity produced: this is called the “strike price”. The strike price is guaranteed and indexed for 15 years, to give investors the confidence to develop projects with high upfront costs and long lifetimes.

Renewable generators can apply for a CfD by submitting a ‘sealed bid’ in a specified auction round every two years, of which the third round concluded in September. Contracts are awarded to developers that bid with the lowest prices.

When the market price for electricity is higher than the contractual Strike Price, the generator receives the market rate and pays the difference to the government; when the market price is lower than the strike price, the government pays the generator to make up the difference.

Notably, prices have fallen with each CfD auction: round 1 strike prices were £114 per MWh (operation start year 2018/19); round 2 prices were £58 per MWh (2022/23); and round 3 = average £41 per MWh (for project starting in 2023/24 and 2024/2025) (all costs are stated at 2012 prices for continuity). There are different categories of technologies under the CfD: Pot 1 (established technologies, such as onshore wind and solar) and Pot 2 (less established technologies, such as offshore wind and biomass CHP). Only Pot 2 technologies have been eligible for the last two rounds.

Why has offshore wind been so successful?

What underpins the amazingly successful investment and development of offshore wind which has led to such low prices? Regen identify the critical factors to be a) public actors working with the private sector, b) a clear policy framework, c) seed investment and d) a clear development path.

These essential items need to be applied in a consistent way across all energy, industrial and business sectors to meet our climate change targets.

What are the possible ramifications of these record low prices?

- Round 3 has shown prices £8-9/MWh below the government’s “reference price”, the expected price of electricity on the open market. If the market follows the government’s expectations, Carbon Brief expects these wind developments could contribute nearly £600m towards consumer bills by 2027, instead of receiving a subsidy. In addition, these prices are so low that the UK windfarms could generate electricity more cheaply than existing gas-fired power stations as early as 2023, much earlier than the expected tipping point of 2030.

- Offshore wind may now be considered as a mature, proven technology, and moved to Pot 1. This may remove it from further CfD rounds.

- The government may continue its stubborn opposition to developing onshore wind energy, despite high public support, as offshore prices are low.

- Innovation continues to thrive: Doggerbank, 130km off the Yorkshire coast is one of the areas contracted under round 3, and will feature the world’s largest wind turbines. Each turbine will be 220m high, with 100m long blades, and a third more powerful than current, typical turbines. Each turbine is expected to generate enough electricity for 16,000 homes.

- Larger, more efficient turbines and improved design and operation will increase the “load or capacity factor” for offshore wind to over 50% by 2035 (currently 39-47%) according to research for BEIS, meaning more energy will be generated, cleanly and cheaply. The capacity factor is the average power generated, divided by how much it could produce, over a set period of time; the higher the value, the more power has been generated. For wind power, factors that lower the capacity factor include windspeeds that are too low or too high; turbines not working; system losses e.g. energy lost in cables; and the ability of the turbines and their layout to capture the available energy.

Could offshore wind farms be built without any public assistance?

The Financial Times argue not, unless the cost of intermittency is significantly reduced. While the round 3 developers will be paid at rates less than estimates of future market prices, they still have a guaranteed price and buyer, and do not cover the cost of intermittency (curtailment costs and the need for backup electricity sources) and network and grid connections.

Forcing renewable generators to cover these costs may increase the required subsidy but would encourage renewable power operators to reduce the cost and impact of intermittency issues. Further it would be a more transparent approach, enabling a more accurate comparison of different power technologies.Integrate believes that achieving a fair and transparent process is ideal, but the same goal needs to be applied to all power generating sources, for equity. For example, nuclear power operators should fund long term waste disposal and fossil fuel companies would need to cover the cost of spills, contamination and decommissioning, as well as climate change induced impacts. Due to vested interests, powerful lobbyists, and slow nature of policy changes, it is unlikely that there will ever be a fully transparent, even, playing field on which to compare power generators.Arguably, a better approach would be for the government to allow Pot 1 technologies to compete in future CfD auctions i.e. solar and onshore wind to give them the same opportunity to produce zero emission energy for our net zero future.