The Just Transition And Net Zero Triad: Law, Technology, And Finance

That we live in an unequal world is indubitable. It is also a fact that the expressed desire to reduce global disparities has been an international aim for decades.

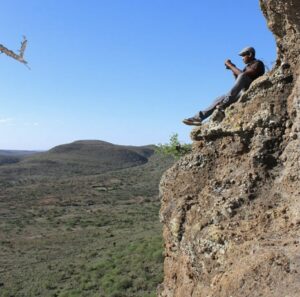

Seven years ago, I started my day by sending emails from a state-of-the-art building in Nairobi, Kenya, with newly installed ‘cutting-edge’ internet infrastructure. An hour’s drive later, I was perched on a different edge. The precipice of a cliff. Watching goats. There was no electricity or modern housing. I had just climbed through the roof of a cave to gaze at the stunning scenery. Today, I write this piece from an ornate site in Central Oxford. Despite being almost 140 years old, its interior has dazzling light fixtures, other modern equipment, and rapid internet. Meanwhile, at the end of 2021, the landscape in Loodariak is still dotted with livestock, few modern houses, and a wind farm. Most of the pastoral community there still do not have access to electricity and all other contemporary conveniences.

Millennium Development Goals and Sustainable Developments Goals are some international initiatives that were launched to level the inequalities between societies or (more realistically) to abate the suffering of the poorest and most vulnerable populations on earth. However, modern development is powered by the energy sector, which is still heavily reliant on fossil fuels. The continued use of fossil fuels is characterised by depletion of natural resources, pollution, anthropogenic climate change and inequality. Therefore, sustainability or sustainable development (defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’[1]) appears to be an oxymoron. For how can a bustling global population experience greater growth and consumption without depleting natural resources and degrading the environment? This piece proposes a trio of complementary tools that will accelerate the just energy transition to address this challenge.

Law can either be an enabler of sound transformation or a barrier to sustainable change. But the law is often a missing element, or an afterthought, in just transition discourse. The intersection of law and technology is becoming increasingly important, however, they often conflict. With different levels of development, energy innovation generally outpaces legislative processes. Furthermore, smart systems (supercomputing, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and data centres) are new innovations that are not fully understood and are poorly regulated. Similarly, Blockchain and its application in energy holds great promise for the energy transition (especially in developing countries) but may create as many problems as solutions.

Legally binding financial commitments may accelerate the just transition to a low carbon economy. A private sector alliance unveiled the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero at COP26. It comprised of over 450 financial institutions representing assets of more than $130 trillion across 45 countries. They intend to mainstream science and technology in their Net Zero strategies. Arguably, the Alliance needs an enabling legal environment because private finance has not previously featured at UN international climate change talks. Also, the need for legal certainty in this area is accentuated by the reality that public finances pledged in Copenhagen 12 years ago to the order of $100 billion from wealthier countries to developing ones has not been paid. A legally enforceable mechanism would have accelerated the release of that money.

Thus, the just transition may be fast-tracked if its three pillars of law, technology, and finance are effectively integrated in Net Zero plans. Moreover, a just and inclusive transition not only needs these three tools for global cooperation and action but must also allow for diverse strategies that are adaptable to challenges faced by new players in the global energy system.

[1] See, World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future (Oxford University Press 1987).