Fuel poverty in the Brazilian Amazon

Fuel poverty has increasingly been associated with thermal discomfort, health-related issues and winter deaths in the Global North because it forces people to choose between food and a warmer environment. If we juxtapose this concept in the Global South, what can we learn?

Fuel poverty has increasingly been associated with thermal discomfort, health-related issues and winter deaths in the Global North because it forces people to choose between food and a warmer environment. If we juxtapose this concept in the Global South, what can we learn?

Dr Antonella Mazzone of the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Cooling has examined this blind spot, in her paper that links fuel poverty, thermal comfort and cooling strategies in the Brazilian Amazon.

Fuel poverty

Fuel poverty has increasingly been identified as a threat to human health: in 2017 34,000 people died in England and Wales because of excessive cold (ONS, 2018). While the Global North is paving the way for a common understanding of fuel poverty – based on thermal comfort, efficient building materials and energy affordability – little is known about fuel poverty as a heat-related issue in the Global South, especially in those countries where temperatures are consistently hot and humid for most of the year.

High temperatures intensify the amount of air pollutants and aeroallergen, which can deteriorate existing respiratory and cardiovascular conditions. In addition, excessive exposure to hot temperatures and sunlight has been found to link to gestational issues and foetus health in pregnant women.

Up to 4.1 billion people, especially in India, Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, will need indoor cooling to avoid heat-related health issues, but there are few studies addressing cooling as a fuel poverty issue.

The Brazilian Amazon Framework

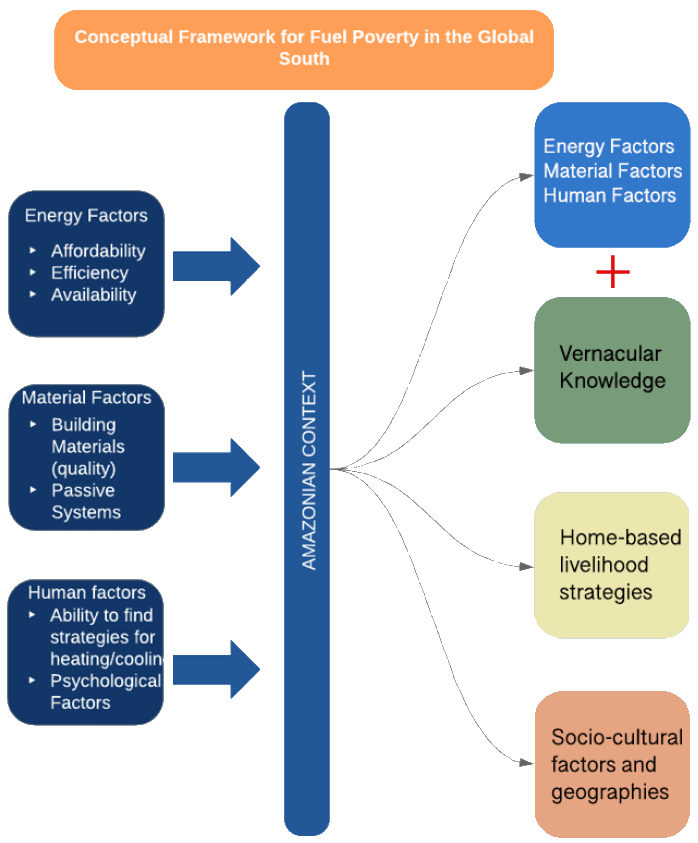

Dr Mazzone has found that the concept of fuel poverty can be applied to the Brazilian Amazon, especially in relation to building materials, household income, energy efficiency, affordability and human physiological strategies.

However, there are differences and Dr Mazzone has created a new conceptual framework for fuel poverty in tropical areas of the Global South, namely: a) home-based livelihood strategies; b) socio-cultural elements; and c) vernacular architecture.

Livelihoods

In many rural areas of the Brazilian Amazon, residential energy services are also used to diversify local livelihood strategies. Energy for productive needs in the residential sector should also be part of the fuel poverty discourse for the Global South as, for many people living in poverty, access to energy can be the only opportunity to escape the poverty trap.

Sustainable cooling methods are fundamental for health and wellbeing in tropical-humid-hot areas. In the Amazon, current livelihood strategies based on the production of local staple food, farinha, are endangering local people’s health and their thermal comfort due to the combination of hot temperatures and smoke inhalation.

Socio-cultural elements

Social factors, such as exposure to air conditioning, human aspirations, tourism, migrations and social status, are also important drivers for cooling services. These can be as important as the need to satisfy physiological thermal comfort, to the extent that people risk their lives when creating illegal electricity connections.

Vernacular architecture

Dwellings built according to traditional or vernacular techniques and material provide effective passive air-cooling. However, the use of modern materials such as metal roofs and cement nullifies this natural cooling, worsening people’s perceived thermal comfort.

While vernacular architecture can be an effective measure to curb the raising demand for unsustainable active cooling (i.e. air conditioners) in hot countries, it seems largely ignored in the Global North, which focuses on tackling winter deaths and thermal discomfort.

This traditional dwelling in Porta Bela has a mix of vernacular and modern fabric. The new materials nullify the effectiveness of passive air cooling and do not insulate the actively cooled air. The home owner has a low income: his air conditioner is second-hand, energy-intensive and inefficient, and he created an illegal electricity connection to use it. He stated that having an air conditioner was the ‘dream of his life’.

Conclusion

Dr Mazzone concludes that tackling thermal comfort and fuel poverty in the Amazon is particularly complex, as it must consider multiple factors, such as vernacular knowledge and natural materials, local cultures, targeted social policies, and, in some cases, desires and aspiration to live ‘like people in the cities’.

Failure to consider the importance of energy relief in the Amazon, and other tropical regions of the Global South, may perpetuate the swift adoption of inefficient active cooling; energy thefts and related casualties, heat-stress and heat-related morbidity; and environmental degradation on a large scale.